Lenskold Article Series

by Jim Lenskold

Marketing ROI Defined

Marketing ROI is one of the terms most commonly used to describe marketing success, sometimes referred to as the holy grail of performance metrics. The financial term Return on Investment itself has a clear definition. Yet there still lacks clarity in the definitions and measures of marketing ROI not only across industries and companies, but even within companies.

I was invited to collaborate with three professors from top universities on a paper to define Marketing ROI. It was both an honor and a great experience to work with these professors that are widely considered among the very best in marketing ROI and measurements. You might think that four like-minded experts would quickly sort through the basics and nail down the definition. Instead, the need for a clear definition became more apparent as we were challenged to come to agreement over many months.

Paul Farris (Darden), Dominique Hanssens (UCLA), Dave Reibstein (Wharton) and I published our definition and the framework to communicate this definition in the paper “Marketing Return on Investment: Seeking Clarity for Concept and Measure.” This article summarizes my personal perspective on the definitions and how some simple variations can help all companies overcome the key areas of confusion and complexity.

The Definition Challenge

First of all, the definition of the ROI calculation must be consistent with the financial definition to maintain credibility with finance. The formula in its simplest form is below. In this format, a positive value results when the profit generated exceeds the cost invested – which is exactly what marketers need to know to manage and improve financial performance.

MROI = (Incremental Profit Generated by Marketing – Marketing Investment) / Marketing Investment

The challenge with establishing a definition for marketing ROI is actually not with the ROI calculation but with the inputs of marketing expense and the financial returns into that calculation. We addressed this by establishing several variations of Marketing ROI that account for differences in measurement precision and timing, along with the specific decision being evaluated. The measurement precision and timing determine how return “valuation” is defined while the decision being evaluated determines the “scope” and “range” of the marketing investment.

Consider the questions below and how these can easily shift how ROI is defined, measured and communicated.

Measurement Precision

- Can you measure or reasonably estimate the marketing contribution to incremental sales, revenue and profits?

- If sales cannot be measured or will come at a later time, can measurements of interim “purchase funnel” outcomes such as marketing response, engagement or inquiries be projected to sales, revenue and profits based on historical averages or analytics?

- Have you run equity analytics that can use measures of short-term outcomes to project future value potential, such as growing a valuable customer base, strengthening the brand positioning or enhancing the business valuation?

- If measurements cannot capture the impact on interim purchase funnel outcomes or incremental sales, can you measure some form of cost savings for comparable metrics such as impressions?

Measurement Timing

- Is the marketing contribution and ROI being measured before potential buyers have progressed through their buying cycle? Longer sales cycles usually require measures of interim purchase funnel outcomes that help project sales volume.

- Does this current marketing investment provide significant additional future value that can be estimated and accounted for as equity?

Marketing Objective & Decision Evaluation

- Will the marketing ROI measurement assess a specific campaign, program or other initiative to prioritize the best among alternatives and/or replace under-performing initiatives?

- Can decisions be split into smaller increments to improve marketing performance? This can include measuring the incremental value of specific elements of a marketing campaign, specific tactics within an integrated campaign or adding additional segments to optimize targeting.

- Will the marketing ROI measurement optimize the spending level along a scalable continuum?

The answers to these questions will guide you to the right choice of the return valuation, scope and range that defines your marketing ROI. All variations can provide reliable insight to assess and improve ROI. A key conclusion from our paper was that communicating the approach is needed to establish clarity and credibility with executives and other stakeholders.

1. Return Valuation Levels

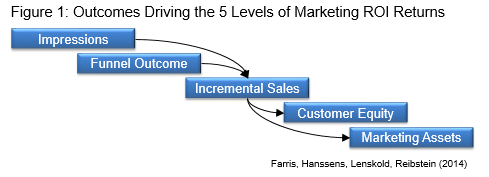

Let’s start with the most straightforward and common approach to the return valuation. When marketing measurements can capture the incremental sales generated, the ROI calculation is run using the marketing expense and the profits from incremental sales over a baseline of existing sales. When you consider the measurement timing, this Baseline-Lift valuation is the central point since some measures value marketing impact prior to a sales conversion and some measures assess future value beyond the sales lift. We established five valuations that are influenced by the timing around incremental sales lift as shown in Figure 1.

Measures of marketing lift on purchase funnel outcomes, such as increased engagement, preference or leads, can be projected forward to future profit in order to estimate ROI. By specifying this as a Funnel Conversion valuation, executives will understand that the profits are either not yet earned or that the measurement precision cannot reliably capture incremental sales.

A Comparable Cost valuation is used to guide marketing decisions that can generate impressions (or other forms of contacts) at lower costs. A good example of this is comparing the cost of generating earned impressions from social media or sponsorships against paid impressions from advertising media. The big assumption required to align this cost comparison to ROI is that all impressions have the same impact on sales and therefore, a lower cost will yield a higher ROI. The cost savings can be run as an ROI calculation (cost savings divided by the original marketing cost for the same number of impressions) although this differs from how finance would typically calculate ROI. I personally prefer to run ROI using the Funnel Conversion valuation for this type of decision, using a best estimate of sales conversion per impression to compare the lower cost marketing to the original marketing.

The other two valuations are inclusive of profits that follow the initial incremental sales. A Customer Equity valuation accounts for the value that a larger or better customer base will provide for future marketing. The Marketing Assets (or Equity) valuation includes the financial value that stronger brands will provide in terms of company valuation and future marketing effectiveness. Equity value in ROI measures can be tricky since additional investments are typically needed to convert this equity into actual profits. But those ROI measures are possible and desirable to reflect longer-term contributions from marketing.

It is important to note that the difference between the Baseline-Lift valuation and these equity valuations is not limited based on timing but on a direct outcome vs. the “potential” for future value. The Baseline-Lift valuation should account for incremental value for as long as that profit stream lasts. It can include future profit streams for multiple years if there is a reasonable assumption that these profits resulted from converting a new customer and do not require additional marketing expenses (such as the acquisition of a 401k customer).

2. Measurement Scope

The inputs into a Marketing ROI calculation must align to a specific marketing decision with an understanding of the context of that decision. The basic principle is to “make more money than you spend” or in business terms, generate enough profit to reach or exceed an ROI threshold (the goal). Marketers make decisions that range from determining the total marketing spend, to choosing which tactics to implement, to deciding the reach, target, offer and creative to maximize the impact of each tactic. The “scope” of the ROI measure simply states the specific marketing initiative being measured.

3. Measurement Range

While the scope defines what is being measured, the “range” defines what that marketing spend represents in the context of other marketing. The terms we established to help communicate the measurement range are Total ROI, Incremental ROI and Marginal ROI.*

Total ROI represents the measure of independent marketing initiatives that stand on their own, whether the scope is a small single tactic campaign, an integrated multi-channel campaign or a major channel investment. The ROI is based on the total marketing investment and the return generated from that investment. This type of marketing ROI measure determines if that initiative is a good use of budget or if other alternatives can generate a better return.

Some decisions are based on modifying or enhancing a base level campaign, program or marketing mix, such as adding another tactic to an integrated campaign, or adding an offer to an existing marketing initiative. An Incremental ROI measure evaluates just the incremental decision separate from a base decision.

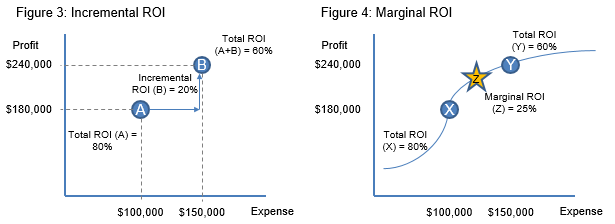

As we introduce the concept of incremental or marginal spend, it is critical to note that the objective is to maximize profits and not ROI. Better decisions are made when measures show these smaller increments of spend have good ROI instead – a fact that could be missed when looking at just the total. Figure 3 and 4 below demonstrate this.

In Figure 3, the addition of the marketing enhancement B (let’s say a second contact) to a marketing initiative A (the initial contact) increases profit but brings the Total ROI down from 80% to 60%. The Incremental ROI shows that the additional $50,000 brought in $70,000 in profit for a 20% ROI. If a company has an ROI threshold of 25%, the decision to add the second contact would not meet that objective. But in other cases where the Incremental ROI exceeds the threshold, the decrease in ROI would be acceptable.

Marginal ROI defines the range for measures that assess many continuous increments to find the most optimal. This is needed when marketing decisions are highly scalable, such as a media purchase. As Figure 4 above shows, the Marginal ROI identifies the optimal point of diminishing returns between X and Y where the threshold is optimized and is not achieved with the next increment of spend. This typically requires advanced models to deliver such precision.

* Note: In my book, I use Incremental ROI for both incremental and marginal since the concepts are the same. The split here emphasizes the different measurement techniques. I also split Total ROI into Independent ROI, the measure of any single initiative, and Aggregate ROI which is a broader total that can roll up a number of integrated marketing initiatives for more optimal decision-making.

Conclusion

In order to achieve the objective of creating a clear, consistent definition of marketing ROI, the marketing community has to come together. Here is my list of priority actions:

- Maintain financial integrity. This definition of Marketing ROI and all variations presented are based on marketing contribution to sales, revenue and profits. Using the term ROI when the return is a non-financial outcome is inaccurate and only hurts marketing credibility.

- Don’t exclude brand awareness investments. One argument against ROI has been that investments into awareness and other short-term brand initiatives cannot easily be connected to sales contribution. However, advertising, social media and other brand investments do influence short term sales and there are measurement techniques to assess this. At a minimum, marketers should be able to create ROI scenarios that estimate where and when those investments will provide a sales lift – including long-term brand equity contribution.

- Think incremental. Most marketing decisions are not about adding or removing initiatives but improving those initiatives. Measurements designed to assess Incremental ROI within a tactic or within the overall marketing mix can analyze how changes to the segment targeting, touchpoint frequency, offers and spend levels can generate profit improvements.

- Expand measurement precision over time. Many marketers are still working toward measuring incremental sales so measurements of customer equity and brand equity may be far off. Modeling and market testing work well to assess sales lift. Analytics to link funnel outcomes to sales help basic results tracking effective at projecting financial contribution. Take steps to prioritize measurement needs and put extra effort to improve measurement precision where the payback is greatest.

- Gain insights from ROI scenarios. Measurement precision can be restricted by data, market environments or budget yet the exercise of running ROI scenarios in the planning stage are always worthwhile. Projecting the profit potential without measurements offers great insight to guide decisions.

I consider the direction of the “Marketing Return on Investment: Seeking Clarity for Concept and Measure” paper to be a huge step forward. The return valuation, scope and return provide the details needed to effectively communicate the variation of Marketing ROI used to measure, assess and improve the financial contribution from marketing. This communicates what is measured and what is not. It aligns the measure to the decision being evaluated. With a well-defined marketing ROI definition in place, companies can build the MROI framework that will guide marketing performance and profitability to higher levels.

Download and read the complete paper for additional detail as well as case examples: Marketing ROI Defined – Full Paper.